Propositional Culture: A View from the Margins -- Part II

Culture Clubs

At the end of my previous article I referred to “the reality of culture”. Rather than taking a view of culture that is similar to so-called race realism, I employed the term to suggest that cultural distinctives are virtually essential to our understanding of who we are. I regard this as undeniable, given the nature of culture, particularly in relation to religion:

Religion. . .is the meaning-giving substance of culture, and culture is the totality of forms in which the basic concern of religion expresses itself. In abbreviation: religion is the substance of culture, culture is the form of religion.1

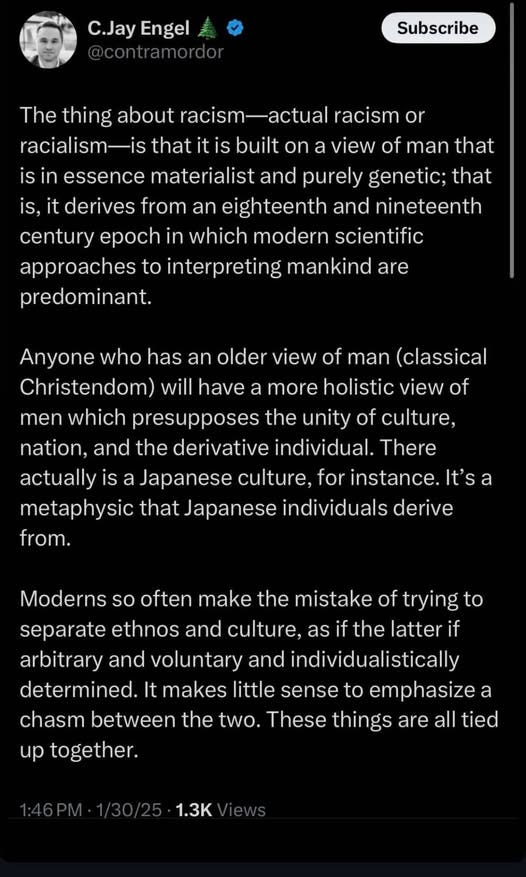

Given this relation, the process of enculturation is a type of religious formation, making culture virtually as essential to our identity as religion. If your religious commitments are not essential to your identity, then you actually do not have religious commitments, or at least not the ones you think you have. Denial of that fact is pretended neutrality. It shouldn’t be controversial to acknowledge this, but that is not the case. Recently, in one of several online groups to which I belong, one of the contributors posted the following tweet (or whatever they are called now):

The almost uniform testimony was that this smacked of racism or kinism. One person in specific objected on the grounds that it expresses “the idea that who a person is is fundamentally tied up in their group identity, specifically their ‘folk’ identity.” He then asked for thoughts, of which I have several.2

Depending upon what one means by “tied up” and “fundamentally”, Engel is not off base in believing that who a person is is “fundamentally tied up”, in his group identity. First, the reduction of ethnicity to a “group” is ridiculous and ignorant. Culture and ethnicity (to the extent they can be distinguished) are not things one simply steps into. You don’t join them like you do a bowling league.3 Consequently, one’s culture actually is rather fundamental to one’s identity, as the experience of Marginal Man attests.

Engel mentions the Japanese. They have the same view he does about the relation of an individual to his ethnic group: you can move to Japan, marry a Japanese man or woman, have and raise children in Japan; but you will never be Japanese. But those who want to accuse Engel of kinism would probably have little to say to the Japanese. I may be mistaken, but I doubt if anyone is going to hop on an airplane and go lecture the Japanese on the evils of their ethno-nationalism. I suspect Christian missionaries will be too winsome to tell the Japanese that among the many sins of which they must repent are the sins of ethno-centrism and ethno-nationalism, which manifest themselves in denying the name “Japanese” to people simply because they weren’t born Japanese.

The denial that you will ever be Japanese will be as much about culture as it is ethnicity (or race) — one might even say, kin. But it is even more than that. I am a white hispanic; I do not mean simply that I am a white man with a spanish surname. I mean hispanic (not latino, certainly not mexican-american). As a child, when I went home from school — week nights, weekends, holidays, and especially summers — I might hear very little english until returning to school. Much of the music, many of the TV shows and movies we saw were produced south of the border. And although he grew up (so I believe) in California and I grew up in Texas, George Lopez and I had just about the same exact childhood. My wife and I, despite growing up a few hundred miles from one another, had very dissimilar childhoods. She grew up in north Texas (Dallas metroplex). I grew up not very far from San Antonio (as Texans measure near and far). We grew up in the same state, but not the same world. Even after 35 years of marriage we can experience culture clash in our living room: we do not always experience the world in the same way; it therefore takes a bit of negotiating to come to a shared understanding of the world we now share together. And that still does not always happen easily. The relation between the human and his culture is thick.4

Whether or not you agree with me (or Engel), the fact is these differences at least feel metaphysical and fundamental. I don’t know Engel personally, but I have interacted with him a few times on X (Twitter). He has never struck me as a kinist; perhaps he is. But the fact is, for many people, there is something almost metaphysical about ethnicity and culture, not because we are “tied up” in our “group” identity, but because our so-called group virtually creates us.

I suspect, in this objectionable tweet, CJ is on about the fact that there are those who seem to believe in something which one might call a “proposition culture”, which would comport nicely with the silly notion of a “proposition nation”. It makes sense. Since there is no such thing as a nation without a culture, a proposition nation would therefore, and necessarily, require a proposition culture, those propositions being contained in our founding documents — which, oddly enough, are not products of a proposition culture, or nation.

In contrast with my view, most of the comments in the group chat lent credence to something Anthony Bradley said to James White a few years ago, paraphrasing: only euroethnic (hereineafter, white) people have the luxury of pretending not to see race, ethnicity, and culture. For the rest, that has not been possible, and pretending that such things are no big deal is not the charitable move some whites seem to believe it is.

Whatever Engel’s actual commitments are, it is not per se kinist to have the view he expressed in this tweet. Frankly, the rest of the world feels the same way; only white people are required to affirm a different view. Those of us who are not — strictly speaking — white (as an ethnocultural group) have a high view of our cultures. We are happy to live with, and to love, even to marry, outside of our ethnocultural groups (hereinafter, ethnicity); but we are not white, and the denial that there is something fundamental about one’s ethnic distinctives, only means that non-white ethnic distinctives are equally as unimportant to whites as are their own ethnic distinctives.

Those wishing to deny the reality of culture as an essential part of one’s identity might consider that the phenomenon of culture shock lends credence to the claim that the relationship between the individual and his culture is so thick as to be metaphysical, or at least experienced as such. We can see this in the common three phases of culture shock, an experience one can have just by traveling abroad, for example as part of one’s educational experience:

The Honeymoon

During this initial period one might feel excited to make the trip, enthusiastic about trying new things and exploring the host country.

The Rejection

Eventually the awareness of not being a tourist sets in. One is, after all, here to work. And everything is work, not just school, but the new relationships — frankly, everyday life. It may take one longer to study or to do one’s job due to language differences: as with english, the foreign language you mastered in school, is not the language actually spoken on the street, or the classroom, or the office. As cosmopolitan as you would like to be, and to your own surprise, you might actually feel homesick. Anxiety and depression are not uncommon experiences. You may begin to withdraw from your new friends and associates, who, however friendly, see you as an outsider. If you are an american in europe, get accustomed to condescension: even if you have a PhD, the taxicab driver will think he is better educated than you.5 (Been there, done that. Just saying.) All of this may be worse if you brought your family with you. Children can be so cruel.

The Recovery

As time passes, one is able to enjoy the new surroundings, become more relaxed and self-confident, even begin truly to enjoy life. Adding to this, there will be fewer misunderstandings due to language; mistakes will be understood and painlessly resolved.

I think Flannery O'Connor’ short story, “The Geranium” presents an illustration of the trauma of culture shock. Old Dudley has been dragged from his home in the south to live with and be cared for by his daughter in New York City. The story opens with Dudley sitting in a chair, looking out the window, waiting for the people in the apartment building next door (a mere fifteen feet away) to put their geranium out on the window sill, the only plant life, and only source of comfort in his new world. Seeing the geranium reminds him of home, and he compares it, unfavorably, to the geraniums that Mrs Carson raised. It also makes him think about the Grisby boy, stricken with polio, “who had to be wheeled out every morning and left in the sun to blink.” Dudley struggles to adjust to the cramped quarters of tenement housing. As if matters were not bad enough, Dudley experiences a crisis when a black couple move into the building, on the same floor at that! At first, he believes they are servants, hired by the tenants in the apartment down the hall, and wonders at the financial ability of apartment dwellers to afford servants. He thinks he might ask the man about the best places to go fishing. (All the blacks back home know the best fishing spots.) It would be an understatement to say he is shocked to learn that, in fact, the black couple are the new tenants. Imagine living not just in the same building with black people who think they are just as good as you are, but on the same floor!

But the worst is yet to come. His daughter asks him to go down to the third floor to ask Mrs Schmitt to lend her a shirt pattern, which he does. On the way back up the stairs to his daughter's apartment, he becomes winded and falls down on the stairs. One of the other tenants — the black man — finds him on the stairs, helps him to his feet, up the stairs and to his apartment. Having to be assisted by a black man (who had the nerve to call him Old Timer!) is the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Once returned to his apartment, Dudley makes his way to his chair, crying, and seeking the comfort of the geranium. But it isn’t there. The tenant in the apartment across the way is sitting at the window where the geranium should be, and he mocks Dudley for crying. Dudley asks about the geranium, and is informed that the wind blew it off the sill. Dudley looks down six floors and sees the shattered pot. The geranium, his only comfort in this god-forsaken place, and which he didn’t actually like because it wasn’t properly cared for, is gone.

We may not sympathize with the trauma of culture shock that Dudley experiences. And we may not mourn with him at being aided by a black man, and mocked for crying over his lot in life. Dudley was after all a racist and a white supremacist. Naturally had we been alive back then we would have been so much better.

And the scribes and Pharisees would not have persecuted the prophets.6

It could be argued that I am making too much of culture shock in making my case about the thickness of cultural distinctives. Of course moving, even temporarily, to a new culture can have psychological and emotional consequences, Solís. But that doesn’t justify claims about the metaphysical nature of cultural distinctives.

Perhaps so, but I am persuaded by the fact that the stages of culture shock bear some similarities to the life cycle of the marginal man. We can compare the above-mentioned three phases of culture shock with the three stages of the marginal man’s life cycle (as explained by Stonequist, and discussed in my previous article): introduction (characterized by a lack of awareness of cultural conflict); crisis (awareness of cultural conflict, resulting in identity crisis); adjustment (attempting to cope with the identity crisis). An important distinction, however, is unlike the experience of culture shock, matters are somewhat exacerbated by the fact that the new cultural situation does not put the marginal man in the position of being a tourist or a guest worker. The new cultural situation is to be his new home — forever; culture shock, therefore, does not create a crisis of identity. An American in a foreign country, is still an American. He knows what that means; the people of his host country also know what means. Dudley, whether we sympathize or not, is not in that position. He is a stranger — a permanent resident — in a strange land. And at his age, he will die in that condition.

I said above that Engel’s thesis (expressed in my own words) that the relation between an individual and his culture is so thick that it is legitimately considered metaphysical due to the fact that his culture in a very real sense creates him is undeniable. This raises the question, “How — and why — would anyone deny this?” I am not so certain about the why, but the how has to do with the way in which the denial is stated, which involves a certain framing of the issue. Note that the denial I cited above was not expressed in terms of culture. That is to say the denial was not put forth as, “The relation between an individual and his culture is not thick and is therefore not legitimately considered metaphysical because, in fact, there is no sense in which it can be said that the individual’s culture creates him.” But rather, the denial was expressed in terms of group, rather than culture. That is, the denial was put forth as, “It is false to claim that who a person is is fundamentally tied up in his group — or folk — identity.”

It is framing the matter in terms of “group” rather than “culture” that make the denial not merely possible, but acceptable. Well of course your identity is not tied, metaphysically, to some arbitrary, even nominal, group you belong to. After all, belonging to a bowling league doesn’t make you a Bowler in an ontological sense. Bowler is what you do, not who you are.

To that extent, it is true: the relation of the human to his “group” is thin; no argument there. Matters are much different, however, if (i) “group” is not the proper way to frame ethnicity and (ii) the relation between the human and his ethnicity is thick.

Denying the thickness of the relation between the human and his culture makes no sense when we take into account the relation, described by Paul Tillich, between religion and culture. Taking van Til’s formulation, if culture is the externalization of religion, and religion is formative, then culture is also formative. That is, religious practices result in spiritual formation; and so, therefore, do cultural practices, a claim supported by the experience of the marginal man who has distinctive psychological characteristics, as Chavez pointed out.7 Another source of support for the claim comes from disciplines such as ethno-psychology and cultural psychology

Ethnopsychology (or psychological anthropology), examines the relationship between the individual and his culture. I was introduced to the discipline at a lecture I attended in 1992, delivered by William Coulson, who described ethnopsychology as the study of the ways that members pass their culture from generation to generation.8 The process of doing that (i.e., passing our cultures to succeeding generations) is enculturation, the process of learning one’s own culture. Our children do not become members of our culture simply by being born to us; they must be formed into members of our culture. This is why the human child takes over a decade to raise, unlike the animal kingdom. Similarly, those who wish to join our cultures, without having been born into them, must undergo a similar process: they will be expected in their turn, to pass the culture to their descendants. This process is acculturation, the process of learning a new culture; or as we call it when discussing immigration, assimilation. Both processes (enculturation and acculturation), relevant to my argument, are forms of spiritual formation.

Cultural psychology, predicated upon the assumption that mind and culture are mutually constitutive of each other, examines the ways in which culture both reflects and shapes members’ psychological processes.9 Cultural psychologists have taught us, to cite a single example, for purposes merely of illustration, that Americans and Asians have different approaches to matters of self-esteem — among many others. In at least one well-known study Americans and Asians were asked to rate their mathematics ability. Americans rated theirs high, while Asians rated their low. The Asians scored higher then the Americans. This is attributed to cultural differences: Americans tend toward “self-enhancement” (a motivation to see oneself positively) while Asians tend toward “self-improvement” (a motivation to have others view themselves positively). The distinction between these two motivations is most obvious between independent and collectivist cultures. In the former, people see themselves as self-contained entities, and often emphasize self-esteem and confidence in one's own worth and abilities. In the latter, people see themselves as part of their larger society or peer-groups, and are motivated by the desire not to lose face, to appear positively among one’s peers.

That cultures have distinct psychologies should come as no surprise when one considers the fact that passing culture down to successive generations is a process of spiritual formation, which involves shaping the mind, the will, and the emotions. We can deny it all we want, but those denials are cosplay. Who you are truly is fundamentally tied up in your group identity, especially when that “group” is ethnic, an identity formed by your participation (whether by enculturation or acculturation) in the life of that so-called group. After all, you are not just you: others shape your true self, not only through the relationships you have with them, but with the relationships they in turn have with others. It is an accepted truism that we are the average of the five people with whom we surround ourselves. In fact, it is worse than that: we are the average of tens and hundreds of people we have never even met, including when it comes to our health.10

Considering how thin are the relations in our extended networks, it makes sense that this would be true when it comes to culture, into which we are formed over a period of years. We are in fact, fundamentally tied to our group identity.

Some Christians attempt to get around this by saying that, while that is true for before conversion, after conversion it is our identity in Christ that is fundamental to who we are. The fact is, our ethnicities do matter: they are results of God’s providence, and for His glory. When John surveys the heavenly scene he is able to distinguish people according to their nations, tribes, languages and so forth: those distinctives are discernable even in heaven. And they matter enough for John, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, to draw our attention to it.

The simple fact of the matter is, there is only one ethnic “group” or “folk” that is not permitted to think of themselves as belonging to a people, one ethnicity, or family of ethnicities whose members are not allowed to believe that who they are is, somehow, fundamentally tied up in their “group” identity. I will give you a hint: It is not the “group” of people to which Anthony Bradley belongs, who so believes that who one fundamentally is, is indeed tied up in his “group” identity, that if you also belong to that “group” but do not toe the group’s ideological line, Dr Bradley will call you an “oreo”.

Engel’s critics are mistaken. In all the ways that matter, who we are fundamentally is tied to our ethnocultural groups. The relation between an individual and his culture is thick.

Note: This is the second of what I anticipate will be a four-part series. The first part is here.

Paul Tillich, Theology of Culture (Oxford University Press, 1959), 42. Similarly, Henry van Til observed that culture is the externalization of religion.

Which views I shared to the chat group in highly abbreviated form.

“The building block of ethnicity are (1) a shared name, (2) a shared sense of place, (3) a shared sense of the past, (4) a shared sense of belonging or kinship, and (5) a widely shared set of beliefs and values that give rise to a shared set of practices and norms.” Steven Bryan, Cultural Identity and the Purposes of God (Crossway, 2022), 43.

The term, “thick relationship” refers to a close, deeply connected relationship characterized by strong emotional bonds, mutual obligation, high levels of intimacy, and a significant degree of shared experiences, often seen as the type of bond found within family units.

In his defense, in this day and age, he just might be.

Cf. Matthew 23.31.

See also, Eliverio Chavez, “The Relationship between Chicano Literature and Social Science Studies in Identity Disorders,” Céfiro: Enlace Hispano Cultural y Literario, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Spring 2003), 7 (available, free and in english, here).

Dr. Coulson had worked with Carl Rogers on a rather famous experiment in the 1960s, exploring the role that Rogerian “encounter” or “sensitivity” groups might play in self-examination. This exploration resulted in the destruction (and I do believe that destruction is the correct term) of the 560-member Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in the space of a mere 18 months. Explaining how this happened formed the substantial part of Dr. Coulson’s lecture. Anyone at all involved in ministry should study up on that. See “The Story of a Repentant Psychologist,” here. See also Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan, Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence, (Naiad Press, 1985), esp., 181-93. Although this book is not primarily about the experiments, they do come up at times. (And for those of us in the PCA, this affirms the absolute necessity of shutting down Greg Johnson’s gay Christian pastor nonsense, which I wrote about here.)

“[S]elf esteem is literally sociopsychological. It is psychological because it entails subjective experience, mediated by a host of psychological processes (e.g., self-enhancement in America, and criticism and subsequent attempts t improve the self in Japan), but it is also social and collective because both the subjective experience and the underlying psychological processes can fully sustain themselves only when immersed in the appropriate cultural context. This inevitably raises the question of what will happen to those who are bicultural. There is a distinct possibility that people develop multiple sets of psychological processes that are attuned to different cultural contexts and become capable of switching back and forth between them as they move to different cultures. And indeed it is not uncommon that an American who is an expert about Japanese culture and, like many others in American academia, is assertive and outspoken on home territory becomes docile, subdued, and deferential when working in Japan and interactive with Japanese colleagues. The reverse pattern may also be found for some Japanese working in the United States.” Alan Page Fiske, Shinobu Kitayama, Hazel Rose Markus, Richard E. Nisbett, “The Cultural Matrix of Social Psychology,” (available here) in D. Gilbert, S. Fiske and G. Lindzey, eds., The Handbook of Social Psychology, (4th Ed), pp. 915-81, at 944.

This is the conclusion of a 32 year study, evaluating a network of 12,607 people, by Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler, who found that, “[n]etwork phenomena appear to be relevant to the biologic and behavioral trait of obesity, and obesity appears to spread through social ties.” See Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler, “The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network over 32 Years,” 26 July 2007, New England Journal of Medicine (Vol. 357, No. 4), available here. Christakis and Fowler do not argue that one “catches” obesity. Rather the obesity is the result of adopting the habits and lifestyles of those with whom we spend time and who, in turn, spend time with others we do not know, and which is a function of human neuroplasticity. Culture, I argue, operating on a more fundamental level — forming our minds, our wills, even our emotions — is a set of habits and dispositions.